After transforming my Spring 2020 university courses from face-to-face to online delivery right after spring break when the COVID-19 crisis really took off in the US, and after teaching a summer course, Introduction to Literature, online, my husband and I finally left the house for a quick, safe summer break. Our destination is Mayhill, New Mexico, up in the Lincoln National Forest area. We had vacationed there 36 years ago (where does time go?) when we were becoming a serious couple and took my 4-year old son, Brad, with us for a visit to New Mexico. We had gone to Carlsbad and spent the night with my Grandma and gone out to the farm to visit with my Uncle Julius, and then to the Carlsbad Caverns. Then we had headed up to Mayhill, outside of Cloudcroft, and rented a cabin to do some hiking and sightseeing, going down to White Sands and Alamogordo and looking in at the Rocket Museum. I had been driving a little red car that overheated going back up to Cloudcroft and we had had to pull over and let it cool off. We stopped at a look-out spot and I snapped a picture of Brad and Wally on the guardrail.

This time, Wally and I are going alone to the same cabins, The Lazy Day Cabins. We want to get away from our computers and get up in the mountains to refresh, hike, and take it easy. Just as we were getting our supplies together, Wally found out that New Mexico had decided to quarantine visitors from Texas because Texas’s coronavirus numbers were escalating. A moment of stomach clenching, thinking of plan Bs if we could not escape. Then Wally contacted the owner of the cabins and we were reassured that our plan to hike and shelter in the cabin would be fine. In fact, we saw quite a few Texas license plates, so we were not alone in tempting the law.

So, I turned in grades and then we were off. We left Kingsville at 7 a. m.—a record for us—no returns to the house to gather forgotten things. On the road, we got through San Antonio, and then onto Interstate Highway 10 headed west. Long and straight, it connects the east and west coasts and follows some of the old trade routes between San Antonio and El Paso. It is interesting that cities like San Antonio seem to be a hub where geographic terrains change. Going west out of San Antonio, you are in a different terrain, leaving the flat, greenish landscape south of San Antonio, skirting the hill country and then down onto the flats of west Texas, the scrub becoming sparser and sparser, mesas occasionally outlining the horizon, wind turbines competing with oil pump jacks in the landscape. Not much else to see from the freeway. The road is straight, the horizon is wide, with lots of room for contemplation or just staring and not doing much (unless you are doing the driving). Just the thing for forgetting the hurry-scurry of classes, computers, and everyday life.

We took a side trip to Ft. Lancaster, between Ozona and Ft. Stockton. Of course, the fort was closed because of COVID, but we had a nice picnic at the scenic overlook. It looked like Fourth of July revelers had been there before us and left some of the remains of the fireworks they popped off the rim of the overlook. The fort was located along the old roads first used by Native Americans and then adopted by US travelers and troops to move goods between San Antonio and El Paso, to transport troops during the Mexican War and goldminers headed to California. Fr. Lancaster was part of a chain of forts along our route meant to safeguard Americans from the Native Americans—Apaches and Comanches-- who also claimed the region. The fort is situated in a wide valley between hills; looking at it from the overlook you can imagine the trail they would have taken. Now it is a quiet, solitary space. Fresh air and quiet after so many months at my home computer. There really is something freeing about the wide western desert landscape, as long you are just passing through. I don’t think I could live in the area, but it is refreshing to view it.

Then on to Fort Stockton, another fort established in late 19th century to protect transportation routes and Euro Americans from the Native Americans. The Texas and Pacific Railroad line ran through there; it is interesting how many of the West Texas towns are centered around forts and the railroad. My great grandparents, Hugh and Lucy Petty, lived in Ft. Stockton and mother used to visit them often as a high school girl in the late 1940s. I remember seeing a sweet photo of me and a cousin, Mike Conley, both of us around three years old, sitting with our great grandparents in a metal rocker under the trees (pecan?) in their yard. Wally and I got off the freeway to drive through historic downtown Ft. Stockton, fairly typical of small rural towns--a few historic buildings, a bank, some hair salons and “boutiques,” karate schools, car shops, and a lot of vacant buildings. Then we drove the old Ft. Stockton Historic Drive, stopping for a peek into the guardhouse. The chains hanging from the wall, the small cut-out windows at least 12 feet up, the limestone building and gravel floor let us quickly understand that spending time there must have been brutal. When we stopped, it was 100 degrees outside. A quick run through McDonald’s for some iced tea, and then back on the road to Pecos, our destination for the night.

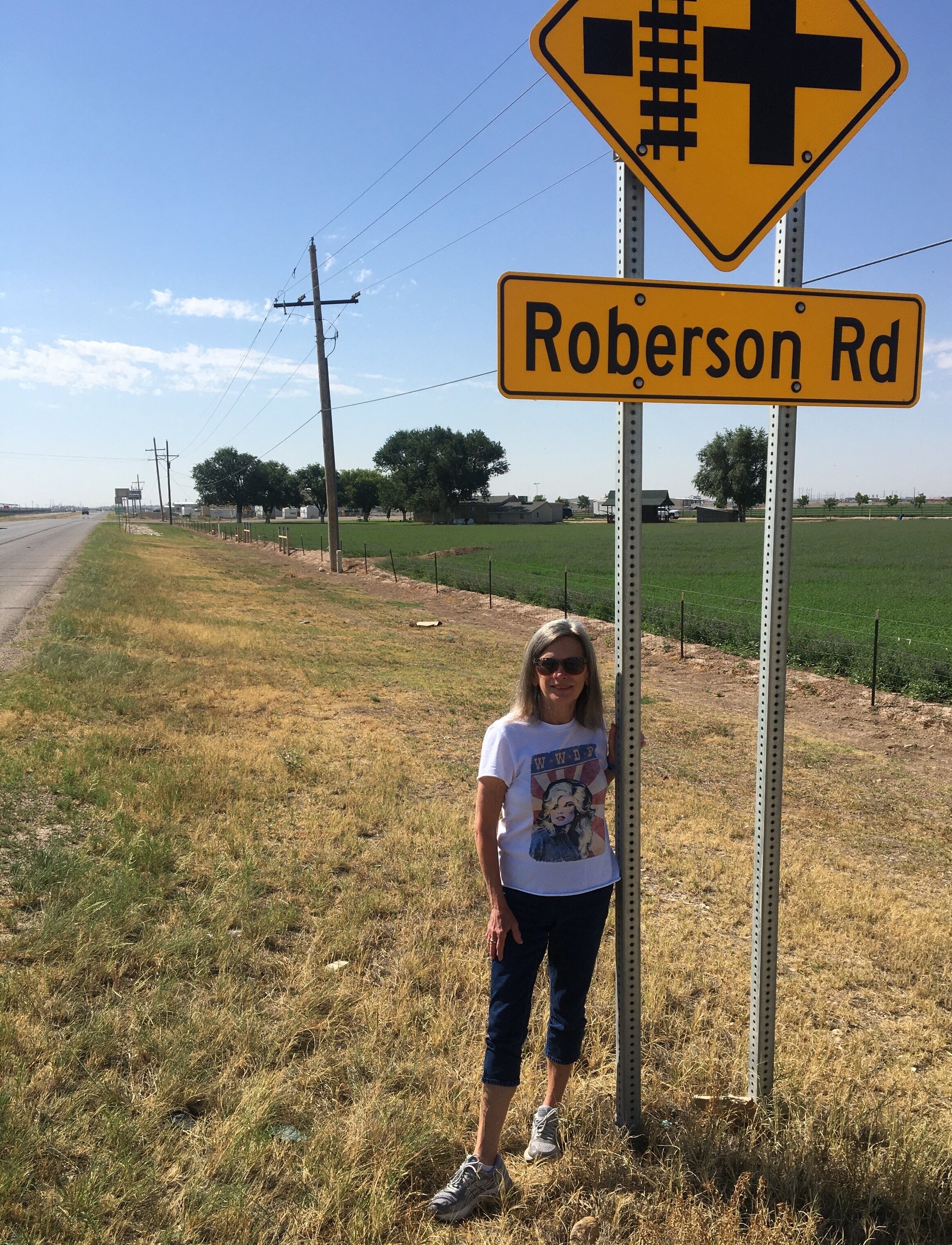

When I was an undergraduate at Baylor University in Waco, Texas and my parents were living in Jamaica, I had to visit my Grandma Roberson in Carlsbad for a holiday—spring break or Thanksgiving, I don’t remember. What I do remember is that I took a Greyhound bus across Texas and into southeastern New Mexico. As a young woman in the late 1960s this was a bit dicey, given the gender politics whereby a young coed was fair game for lurking, lecherous men hoping to get something going on the Greyhound. Well, we got to Pecos at about two o’clock in the morning for a layover. Here I was, 18 or 19, left in a Greyhound station in dark, dusty Pecos, Texas, naïve, apprehensive. I was the only woman, a white woman, left in a sketchy station with a Black guy and a Mexican guy. At that time, it was intimidating to me. Nothing happened, but I obviously remember my sense of vulnerability with those large men of color. It is interesting how you remember a scene from your past and then when you pull it up again, you think about it differently, check the racism inherent in your remembrance of these men. This time when I got to Pecos, Wally and I checked into our motel, wearing our masks, and then ordered pick-up dinner from Alfredo’s Restaurant to bring back to the motel room. Wally had a beer and I drank some wine from those little plastic bottles that come in a wine four-pack. No eating out on this trip.

Leaving Pecos, I was struck by how totally the area—the Permian Basin—is an energy zone. Lots of old-fashioned oil jacks. My mother tells the story that when she and my brother John, who was about four, drove from Corpus Christi to Carlsbad she made up a song to keep him occupied in the days before our family had radio in the car. The lyrics went something like this: “Pumping oil, pumping oil, up and around, from the ground.” Now there are tanks, pipelines, telephone and electric lines, huge transformers marching in a line across the landscape, processing equipment and deep well equipment, signs, and lots of “man camps.” A few solar energy farms but no wind farms here. In town we saw many RV parks for the men, some with coverings to protect the RVs from the sun and heat. We saw several lodging lots, rows of plain, brown mobile homes or tiny homes sitting barracks style on the barren gravel expanse for the men who work in the great energy zone. Some of the camps, particularly those between Pecos and Loving, advertised a cook, wifi, and other amenities. But it looks to be bleak living, no greenery or recreation visible. One imagines these guys just work out in the sun and weather and then go to their mobile home or man camp, drink some beer, watch tv, and then do it again the next day. I hope they rotate on- and off-weeks between home and work.

The terrain out here, between Pecos and Loving, is flat, dusty, a few rises, a few draws. You know you are in West Texas/New Mexico when a creek, with or without water, is called a draw. The plants seem to be short mesquite-looking bushes, some yucca, cactus. Lots of rocks. The sand is a bleached clay color that fades to beige. If it weren’t for the poles, silos, tanks, and pump jacks, there would not be much in the way of vertical vision. The sky is blue, a dusty blue near the horizon, brighter overhead, with a few wispy clouds. This desert terrain will vary to some degree as we travel toward the mountains, more or less vegetation, more or less flat. Sandy, dusty. A wide horizon, a lonely place—except for the vehicles and structures devoted to oil and gas. Right now, the road between Pecos and Loving is busy, but most all of the vehicles are some sort of truck. Pickups, gravel trucks, trucks hauling pipes, tankers. A few lonely taco trucks sit on the side of the road, no doubt for the hungry breakfast and lunch crowd that spills out from the distant job sites, their dusty roads disappearing off the horizon from the highway.