New England Vacation, 2023

Having read Thoreau’s The Maine Woods, I wanted to hike the trails of those woods, even if I would not approach the wilds of northern Maine or Mt. Ktaadn, whose ragged heights sucked a moment of existential crisis from him. And I wanted to revisit Concord and breathe once more its ethereal air made rich by its geniuses, to peer over the Concord Bridge as Henry James had done and imagine the ghosts of Emerson, Thoreau, Fuller, Hawthorne. And to peek into Emily Dickinson’s home, to see her room and gardens, to look out her window where she might have seen a bird come up the walk below. But I did not know that the sea, the great Atlantic, would hold me staring and thinking about its fierce and beckoning vastness, or that the voice of Herman Melville’s Ishmael would keep resounding, asking me to feel the pull that the sea had on him.

After an early flight out of Atlanta and delays in Baltimore, we finally landed at Boston’s Logan Airport, picked up our rental car and headed for Concord. First things first, we grabbed some lunch at the Main Street Café, walked over the Concord Bridge, and then went in search of Thoreau and Walden Pond, now a recreational area with a $30 parking fee that kept us from going down for a quick look. Instead, we headed for Emerson’s house, which was closed, and finally landed at the Concord Museum just thirty minutes before closing, but enough time to look at their replication of RWE’s study and displays of Thoreau’s desk and surveying instruments. I have been to Concord a few times, the first in 1985 when I was researching Emerson for my dissertation and touring with Wally and five-year old Brad. Then in 2003 for the Emerson Bicentennial. Those of us participating in the Bicentennial panels were invited into the Emerson house to wander at our leisure through his home, his library, to sit in Mr. E’s chair. And I had taken Cameron later that year when I attended the American Literature Association meeting in Boston. We had taken the train out to Concord and then walked down to the Alcott house to see the room where Louisa invented her stories. The air of Concord, with its rich history and intellectual vibrance is almost enough to refresh the mind and inspire further lines of inquiry. I wanted to stuff my already full bags with books, more books.

Then to Portsmouth, NH for our first night. We checked into a quirky motel undergoing renovations, and then ventured to the once-bustling ship and submarine building harbor, the gardens there with extravagant flowers and twisted trees, signs of the New England landscape and ethos we would glimpse in our week’s tour.

Downtown Portsmouth is an old town with narrow streets, houses that begin at the sidewalk, no lawns, all right angles, wood, hugged in close on themselves and with other houses, a defense against the cold of winter? Or other hostile forces? Yet, it is also a thriving city, our dinner at a local spot that had been featured on Guy Fieri’s Diners, Drive-ins, and Dives.

The next morning, we walked around the Urban Forestry Center, an introduction to the lush plants and diverse trees of New England, before driving to Boothsbay Harbor.

A stop for lunch at Day’s Crabmeat and Lobster shack along the highway; I had crabcake sandwich and Wally had fish and chips while we sat outside at picnic tables and looked on at the marsh beyond. Part of the fun of travel is eating at local establishments like this one. Blueberry pancakes with real maple syrup and blueberry muffins for breakfast, hot lobster roll at Bar Harbor, some of the local tastes we tried.

At Boothsbay Harbor, Maine, I began to feel the pull of the sea, to contemplate what it means to be a people of the water.

Our motel sat on a pier jutting out into the harbor, so we literally slept over the water. The restaurants all have a view of the harbor. We took a harbor cruise that introduced us to the coastal world of boats, lighthouses, lobster traps and vacation homes. This is a land of the vacationer, of seasonal grand homes in the updated colonial or Victorian style hovering at water’s edge, between woods and water, modernity and recluse. Henry James bemoaned the transition of New England farms to summer homes, of Newport to a showcase of the very rich, their homes compared to white elephants. How much money must one have to support a seasonal home on a small harbor island? What do they do all season? Boat, hike, drink, gossip, spend money? And what of the towns that support these seasonal, summer folk? How many times a day does the crew of our harbor sightseeing boat run the same route, say the same things, repeat the same jokes for an audience that changes only the particulars, but made up of elders, retirees, and young families with eager children whining, “There is a whale watching tour, Daddy can’t we go on the whale watching tour? Please, please.”

Being so close to the harbor and the waters beyond, I wonder, what is it like to be a people of the water, like the characters of Sarah Orne Jewett’s fictional Dunnet Landing who read the ocean’s moods and move causally between land and sea? What is it like to also be a people of the forest, of The Country of the Pointed Firs? To have sea and land jointed together, the boundary between wood and water a sliver of jagged rock, a change from green to deep gray, the dark green of pine and fir and oak lighted in the summer by vibrant colors of flowers blooming for a season—yellows and pinks and reds—of berries decorating dark leaves of holly and currant bushes; ragged rock islands with a lone house and lighthouse, long abandoned and turned into historical monuments, now part of the landscape and the historical memory. What must it be like to teach your kids to lay lobster traps, like the grandfather in yellow rain pants we saw taking a young boy out in the boat to haul up by hand a trap to check for lobsters for dinner or for trade? To have the water as a highway and arena of activity, of income, of identity? This is such a foreign concept to me, land-bound as I have always been despite the beaches I have known. To be as familiar and comfortable in a boat as I am in a car.

The late afternoon harbor tour is a reminder of other boat tours we have enjoyed as a way of experiencing new places—Lake Windemere, the San Juan Islands of the PNW, the Thames River that made me rethink my image of London as a river town with business and transport centered on the water, the Seine River at night. These tours become an integral part of the trip, a new way of thinking about place and identity, of how one experiences life along and on the water.

At Acadia National Park, standing on the bolder ledges of ThunderHole. Watching the waves come in, splash against the ledges, loom up the narrows to the hole that groans and spurts water as the tide rises bit by bit. Watching the ocean coming in, spraying and smashing against the rocks, withdrawing and doing it again, over and over, the insistent pull of the ocean, I get a different sense of Melville’s Ishamael who needs go down to the sea—I had focused on the “damp, drizzly November” in his soul that propelled him seaward, but now have a sense of the pull of the ocean whose sounds and movement, whose depths and mysteries drew him to it.

Then when we went on the whale watching trip, finally after two cancellations because of bad seas and persistent fog. Even on a commercial tourist vessel with 400-500 other people on board, I felt some calm lure as I sat on the side of the vessel and watched the ocean spread out before us. It seemed less like fluid water than a silver surface upon and below which things happen, where life and its dramas are enacted. It was still foggy and chill until we got about 25 miles out, and then the sun broke through warmly, the sea calmed and then broke as Minke whales, Humpback whales, Atlantic white-sided dolphins broke the water as they curved up for air and then curved down under the water’s surface. A fin, a tail, a spurt of water, “look, look” from the passengers, and then quiet. And then again, and further again. Eyes scanning the surface for the elusive sighting, except for the teenagers who ate chips, looked at their phones, and napped in the large inner cabin.

Passing by a lone rock island to get a view of seals sunning themselves, where a lighthouse and lone house stand, now occasional home to scientists and students, no longer the desolate, isolated home of a lighthouse keeper, wife and kids—way out on a small rock island with no vegetation 25 miles from land. How did they retain sanity? Or did they?

Another defining character of Maine and Acadia is the land, shaped by granite and the tectonic shifts that separated the island park from Scotland. Stunted, gnarled trees finding foothold in the shallow bits of soil; flowers tucked in between rocks bringing color and a wisp of fragility to that hard surface. Rocks, boulders, and granite surface seemingly everywhere.

The glorious views from atop Cadillac Mountain, the highest mountain on the Atlantic coast, views to the west catching the setting sun and out to the Atlantic Ocean shrouded in a fog bank. Either way, sights worth the required reservation to drive up the Cadillac. Folks wandering about the stone top, smoothed and guttered by time and wind like the pate of a wizened soul who has seen the beginnings of time.

We enjoyed hiking in Acadia, the paths wandering through forests, along ocean and lakes, walking sticks to help our old knees over tree stumps and across creeks. But bouldering up a trail from Jordan Pool, almost at a 45-degree angle, just about did me in, my knees not what they used to be, huffing, stopping, but continuing on and up. I did almost 18,000 steps that day.

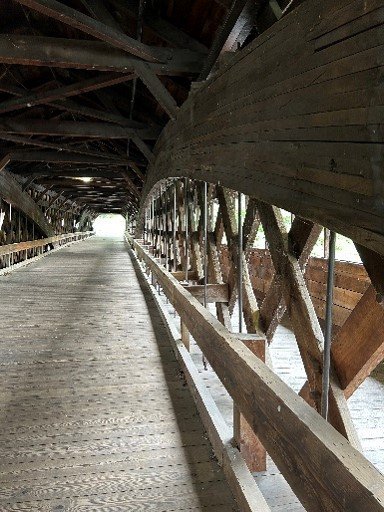

A stop in Bangor to see some of the Stephen King sites and then a rainy drive to Woodsville, NH, skirting the White Mountain area, part of the wide loop we made around New England. Didn’t see much beyond the trees that line the road, the occasional glimpse of lakes, rivers, ponds, farms and village fronts. No real sense of the mountains from where we were, not like the Rocky Mountains that instantly loom on the horizon as you make the turn from Raton Pass to Colorado. After we checked in to the Nootka Lodge and the rain had let up, we went poking around the town, investigating two of the covered bridges and marveling at the architectural and technological beauty and strength.

The other village had a memorial to the local men who plaques had gone to war down the ages, so many with the same last name—fathers, sons, brothers, cousins—fighting wars in distant lands far away from the remote mountain village. I got a sense of the fierceness of the men of rural NH, evidenced perhaps in the “look” so many of the men we saw sported—tattoos, shaved head, long beard, earrings or gauges in their ears. If they are the descendants of the Revolutionary men, then I have a picture of what they might have looked like 250 years ago. I can imagine a guy with tattoos, long beard, and bald head dressed in Revolutionary garb grappling with the red-coated British.

At a Dunkin Donut, a routine stop for coffee, tea, and munchkins, the man at the counter shaved head, bearded, tattooed, and earringed took our order. His crew were a stout older woman (his mother?) and a pudgy adolescent boy (his son?). A family business selling donuts and coffee that belies the rough exterior of owner and most customers. Sitting in the car, waiting for Wally to get his coffee fixed, I saw a young woman with four young children, one in a stroller and three girls carelessly hopping and running around their mother (I assume), the wind swinging their brown hair. Girl power! But then I looked again at the mother, already stout, arm flesh swinging as she walked her brood up the street. Is that what those carefree girls have to look forward to?

Back to Massachusetts for a tour of the Emily Dickinson house, The Homestead, before racing back to Boston to catch our flights home.

Having written a piece on the image and role of animals in her poetry and read about her affair with flowers, I was anxious to see her home and the bedroom in which she thought and wrote such perplexing poetry. The house is renovated, with new wallpaper, carpet, and furniture to match the originals. One is struck by the profusion of color and design in the flowered carpets and wallpaper of the parlor and her room. The conservatory that her father had built to house her bedding plants and more fragile, exotic plants is smaller than I had thought, but still a refuge from the quotidian and the cold. Her room with its small writing desk looking out over Main Street where she could watch folks going to church, look out to the family acreage across the street, or watch the birds she sketched in her poetry, a site of greatness despite its modest size and current neatness.

A replica of her white day dress to evoke her presence stands on a dressmaker’s form in the room, catching the visitor’s eye and asking her to imagine the living poet now gone. “I’m Nobody/ Who are you?” Even so, I did not feel the poet’s presence in her room, not as I had once felt Emerson’s presence hovering behind me when I was writing about him. While the docent capably led the seven visitors through the house and recounted moments from Emily’s life, it was a scripted tour for tourists that while accurate enough lacked a real sense of the poetry or the mind that occupied that house. Still, I am glad to have visited, to have imagined the home when Amherst was still a village.